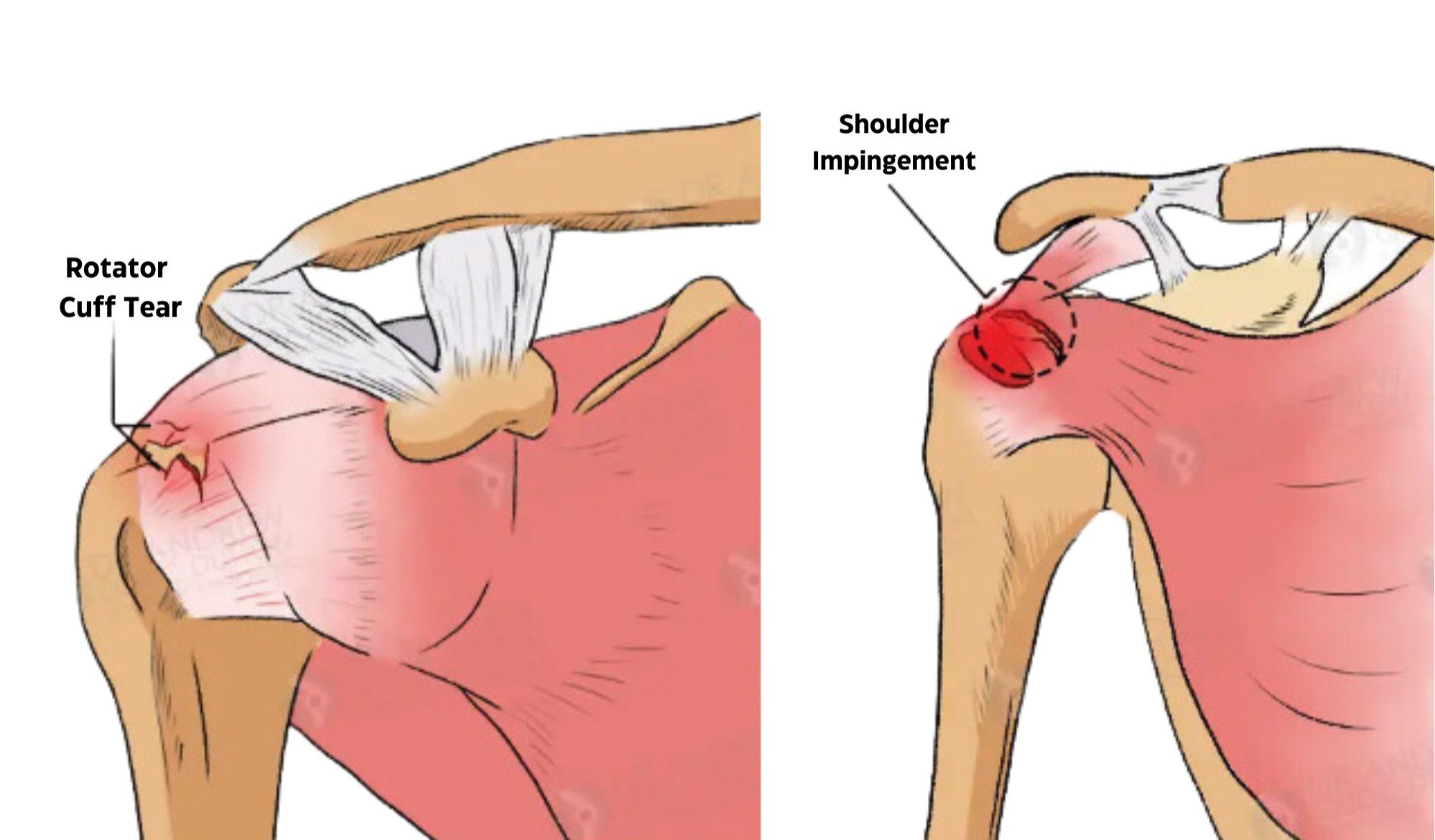

Both shoulder impingements and rotator cuff tears often involve overlapping anatomy within the shoulder complex, which is why these two conditions are frequently confused. However, they represent distinctly different disease processes with unique onset patterns, diagnostic considerations, and treatment protocols. Properly distinguishing between the two is critical for establishing accurate causation, guiding an effective treatment plan, and determining compensability in work-related injury cases.

The shoulder is a sophisticated joint made up of the shoulder joint capsule, rotator cuff muscles, rotator cuff tendons, the humeral head of the upper arm, the acromion, and surrounding stabilizing structures including the shoulder blade (scapula). Even minor alterations to this tightly confined space can result in inflammation, compression, and functional restriction that produces significant shoulder pain.

Overview of Rotator Cuff Anatomy

The rotator cuff consists of four major muscles and their corresponding tendons:

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres minor

- Subscapularis

These rotator cuff muscles and tendons work together to stabilize the shoulder joint, allowing smooth movement of the upper arm during lifting, rotation, reaching, and overhead positioning. Any injury or degeneration within this unit can lead to weakness, pain, and mechanical dysfunction.

What Is Shoulder Impingement Syndrome?

Shoulder impingement syndrome occurs when the rotator cuff tendons become compressed or “pinched” between the humeral head and the acromion, especially during overhead motion. Over time, the undersurface of the acromion may develop degenerative irregularities or bone spurs (osteophytes) that further compromise the already limited subacromial space.

This chronic mechanical irritation leads to inflammation, decreased blood supply to tendon tissue, and progressive tendon degeneration. The supraspinatus tendon is most commonly affected due to its anatomical position beneath the acromion.

Symptoms of Shoulder Impingements

Typical symptoms of shoulder impingements include:

- Pain when lifting the arm above shoulder level

- Discomfort during reaching or overhead activities

- A dull ache radiating down the upper arm

- Night pain, especially when lying on the affected side

- Gradual reduction in shoulder strength and range of motion

These symptoms usually arise slowly as part of a long-term degenerative process rather than following a single traumatic event.

What Is a Rotator Cuff Tear?

A rotator cuff tear refers to a partial or complete disruption of one or more rotator cuff tendons. These injuries may occur in two primary ways:

Acute Traumatic Tears

Acute tears most commonly result from direct trauma such as:

- Falls on an outstretched arm

- Blunt force injuries

- Sudden heavy lifting or forceful overhead movements

These tears typically produce sudden shoulder pain, weakness, and immediate loss of functional strength.

Degenerative Tears

Degenerative tears develop over time due to:

- Chronic tendon impingement

- Repetitive microtrauma

- Age-related tendon thinning

- Reduced vascular supply to tendon tissues

This is where diagnostic confusion arises, as longstanding impingement may progress into partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tears without a distinct acute injury event.

Unlike impingement syndrome, a full rotator cuff tear is often associated with measurable mechanical weakness and compromised shoulder stability.

Distinguishing Shoulder Impingement from Rotator Cuff Tears

Despite anatomical overlap, these two pathologies remain clinically distinct. The most important distinguishing factors include:

Onset Pattern

- Impingement syndrome: Gradual onset related to long-term repetitive stress and degenerative changes.

- Rotator cuff tears: Sudden onset following trauma or slow deterioration progressing to tendon rupture.

Functional Impact

- Impingement: Pain with movement but typically preserved mechanical strength.

- Tears: Pain combined with objective weakness, difficulty initiating arm elevation, and functional instability.

Anatomical Pathology

- Impingement: Tendon irritation from compression by bone structures and bone spurs.

- Rotator cuff tears: Structural disruption of one or more rotator cuff tendons.

Clinical History: Key Questions for Causation Assessment

When evaluating cases involving shoulder injuries and disputed causation, a thorough clinical history is essential. Providers or claim professionals should document answers to the following:

- How long has the shoulder pain been present?

- Has the individual experienced arthritis or other joint degeneration elsewhere?

- Which specific movements provoke or worsen symptoms?

- Was there a single incident that triggered the pain? If so, what occurred?

- Where exactly is the pain felt—localized to the shoulder joint or radiating into the upper arm?

- Is the limitation of motion mechanical, or is it secondary to pain inhibition?

This information often helps establish whether the complaint reflects an acute injury or chronic impingement degeneration.

Physical Examination and Diagnostic Imaging

Physical Examination

Physical exam findings may overlap, as both conditions produce pain with arm elevation. Manual strength testing, impingement maneuvers, and tendon isolation tests can provide clues, but they are not definitive.

Imaging Studies

Imaging is essential for differentiation:

- Plain radiographs identify changes such as decreased subacromial space, arthritic joint surfaces, or the presence of bone spurs.

- MRI offers detailed visualization of rotator cuff tendons, allowing identification of:

- Partial or full tears

- Tendinosis and thickening

- Inflammatory changes

- Signs of acute tendon disruption versus degenerative remodeling

These findings help substantiate whether pathology reflects long-term disease or an acute injury event.

Treatment Approach

Management depends on diagnosis, severity, and clinical findings.

Conservative Management

Most impingement syndromes and minor rotator cuff injuries begin with conservative care:

- Activity modification

- Ice application and rest

- Anti-inflammatory medication

- Targeted physical therapy focusing on posture correction, strengthening rotator cuff muscles, and improving scapular stabilization of the shoulder blade

Advanced Care

If symptoms persist:

- Image-guided injections to reduce inflammation

- Specialized therapeutic protocols through sports medicine clinics

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is considered for:

- Full-thickness rotator cuff tears

- Severe impingements unresponsive to conservative therapy

- Progressively worsening pain or functional disability

Surgery may include bone spur resection, acromial reshaping, or tendon repair depending on pathology severity.

Importance of Diagnostic Accuracy

Impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears may appear clinically similar, but they must be evaluated as separate conditions. Correct diagnosis ensures:

- Proper medical care pathways

- An accurate treatment plan

- Fair causation determinations

- Objective differentiation between acute injury and degenerative disease

Final Considerations

While both conditions involve overlapping anatomy within the shoulder joint, the underlying mechanisms driving these diagnoses remain distinct. Impingement syndrome reflects a chronic degenerative and compressive process, whereas true rotator cuff tears more commonly represent acute structural injury or the culmination of years of degenerative change.

Thorough clinical history, careful imaging interpretation, and objective functional assessment remain essential when differentiating these pathologies—ensuring both appropriate medical treatment and defensible legal conclusions regarding compensable injury claims.